Debate on War in Ukraine

once again: universal capitalism or regional planning?

25th of April, 2022

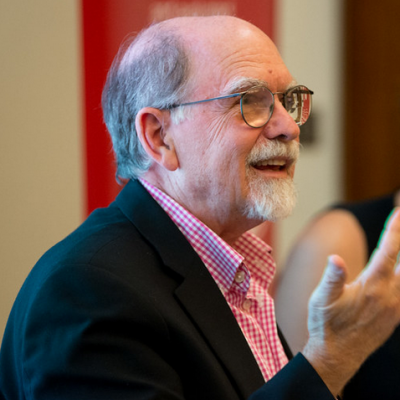

Claus Thomasberger

“World War I … awakened our generation to the

fact that history was not a matter of the past, as

a thoughtless philosophy of the hundred years’

peace would have us believe. And once started, it

did not cease to happen”.

(Karl Polanyi, For a New West, Cambridge: Polity 2014, 29).

A few months before the end of World War II, Polanyi discussed the two principal alternatives on which the post-war order could be established: universal capitalism or regional planning?[1] The path taken at that time set the course that structures international relations to this day. Viewed through Polanyi’s lens, the original sin lay in the utopian attempt to reconstruct after the War an international order that remained trapped in the logic of the 19th century – utopian in the sense that the implementation of such a project would produce unexpected and highly perilous results that unavoidably would frustrate the intentions of the nations involved.

The essay, as well as a subsequent newspaper article[2] primarily addressed the policies of Churchill and other conservatives in England who, bypassing Parliament, sought to distance England from the Soviet Union and tie it (and thus Europe as a whole) to the United States. Polanyi did not attack capitalism in the USA: “Americans almost unanimously identify their way of life with private enterprise and business competition … , rich and poor alike”.[3] His key argument was that capitalism is not an adequate mode of social integration for other parts of the world, and especially not for Eastern Europe. Polanyi had spent most of his life in Hungary and Austria, and during the First World War fought against the Russian army in Galicia (now Ukraine/Poland). The attempts, he understood, to establish a market economy „in multinational areas, like the basins of the Vistula and the Danube, … resulted in hysterically chauvinistic states, who, unable to bring order into political chaos, merely infected others with their anarchy“.[4]

After World War Two, for 45 years, the existence of the Soviet Union prevented the full realization of universal capitalism. This changed in the 1990s after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Universal capitalism was now called globalization. In the rush of supposed final victory, the protagonists of universal capitalism supported in Russia not Gorbachev’s reform project but Yeltsin’s shock strategy. In Ukraine, neoliberal hawks in the European Union, disregarding economic and political relations with Russia, pressed forward with their Association Agreement to undermine Russia’s attempt to strengthen a Eurasian Customs Union.

Today, Russia and Ukraine are capitalist market economies – not exactly as described in textbooks, just “real capitalism” with a clique of oligarchs directly intertwined with politics. In both countries, the conflict between democracy and capitalism has decisively determined the course of recent history: in Russia most visibly in October 1993, when the tanks that Yeltsin had called in put the parliament under fire; in Ukraine in February 2014, when the elected government was overthrown as the result of the Maidan Uprising. Nonetheless, both current presidents were elected by an overwhelming majority. In 2018, Putin won the election with nearly 77% of the vote, a year later, Zelensky with over 73%. And both countries are heavily affected by what Polanyi called – referring to Eastern Europe – the “three endemic political diseases – intolerant nationalism, petty sovereignties and economic non-co-operation … inevitable by-products of a market-economy in a region of racially mixed settlements”.[5]

What are the results of the Russian attack and the Western response in the international arena? Under the wave of new sanctions, the freezing of foreign exchange assets, collapsing supply chains and the need to plan the supply of raw materials, semiconductors and other indispensable commodities, globalization as we have known it has come to an end. And it was a clear signal that in March 2022 the more than 40 states that refused to condemn Russia at the UN General Assembly (votes against and abstentions) represent more than half of the world’s population. Today, with the relative decline of the US and the rise of Asia regional cooperation is back on the agenda. Paradoxically enough, it is not Russia but the Ukrainian people who demonstrate the unbroken importance of national borders and international collaboration on the European level.

Fact is that Ukraine and Russia are part of Europe. The demand to set aside the interests of EU countries in response to the Russian attack shows how much in reality their interests diverge from those of the US. Ending the war is above all a European concern. Solutions can only be found through negotiations. For the European countries it is vital to leave nostalgia behind and face the realities of regional reorganization in an increasingly complex global environment.

[1] Karl Polanyi, “Universal Capitalism or Regional Planning? (1945),” in Economy and Society (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2018), 231.

[2] Karl Polanyi, “British Labour and American New Dealers” (1947), in Economy and Society (Cambridge: Polity, 2018), 226–30.

[3] Polanyi, “Universal Capitalism or Regional Planning?, 233.

[4] Polanyi, 235.

[5] Polanyi, 235.

Claus Thomasberger

Claus Thomasberger is a sociologist and economist. Until 2017 he taught Economics and International Policy at the University of Applied Sciences, Berlin, Germany. He is a board member of the IKPS. His research interests include international political economy, history of economic thought and political philosophy.

Read the other essays on the War in Ukraine here: