Debate on Brexit

Brexit and its consequences

18th of May, 2020

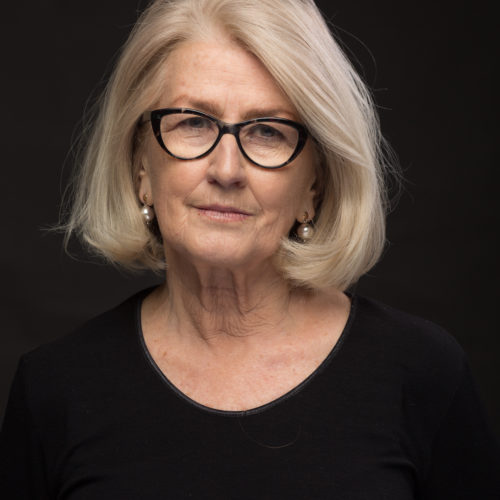

Ann Pettifor

Political Economist and director of Policy Research in Macroeconomics (PRIME)

This text is the conclusion of Ann Pettifor’s Essay ‘Brexit and its consequences’, which has been published in August of 2016. The full text can be read here.

I voted to Remain. I do not believe that Brexit is a wise decision. I fear its consequences in energising the Far Right both in Britain but also across both Europe and the US. I fear the break-up of the United Kingdom, and the political dominance of a small tribe of conservative ‘Little Englanders’. They will diminish this country’s great social, economic and political achievements.

But Britain’s ‘Brexit’ vote is but the latest manifestation of popular dissatisfaction with the economists’ globalized, marketised society. And if there should be any doubt that these movements are both nationalistic and protectionist, consider Donald Trump’s campaign threat to build a wall between Mexico and the US, to deter migrants, “gangs, drug traffickers and cartels” (Trump website). Trump’s plan for financing the wall involves the introduction of controls over the movement of capital. If the Mexican government resisted, argued Trump, the US would cut off the billions of dollars that undocumented Mexican immigrants working in the US send to their families annually. “Its an easy decision for Mexico” Trump wrote in a note to the Washington Post on 5th April, 2016. “Make a one-time payment of $5-10 billion to ensure that $24 billion continues to flow into their country every year.”

Nationalism, protectionism and populism are not confined to western nations. In India, a BJP MP, Subramanian Swamy fired a salvo at Reserve Bank of India (RBI) governor Raghuram Rajan that led to his resignation. Swamy made clear that “the governor should have known the “inevitable consequence of rising and high interest rate and (that) his policy was wilful and thus anti-national in intent”. (My emphasis). The RBI governor’s post Swamy added, “is very high in the Warrant of Precedence and requires a patriotic and unconditional commitment to our nation”.

Karl Polanyi predicted in The Great Transformation that no sooner will today’s utopians have institutionalized their ideal of a global economy, apparently detached from political, social and cultural relations, than powerful counter-movements – from the right no less than the left – would be mobilized (Polanyi, 2001). The Brexit vote was to my mind, just one manifestation of the expected resistance to market fundamentalism. The Brexit slogans “Take Back Control” “Take Back Our Country” “Britannia waives the rules” – represented an inchoate and incoherent attempt to subordinate unfettered, globalized markets in money, trade and labour to the interests of British society. Like the movement mobilized by Donald Trump in the US, the Five Star Alliance in Italy, Podemos in Spain, the Front National in France, the Corbyn phenomenon in the UK, the Law and Justice Party in Poland, Brexit represented the collective, if (to my mind) often misguided efforts of those ‘left behind’ in Britain to protect themselves from the predatory nature of market fundamentalism.

By doing so, they confirmed Polanyi’s firm prediction: that “the idea of a self-adjusting market implied a stark utopia. Such an institution could not exist for any length of time without annihilating the human and natural substance of society….Inevitably, society took measures to protect itself, but whatever measures it took impaired the self-regulation of the market, disorganized industrial life, and thus endangered society in yet another way.” (Polanyi, 2001).

Brexit has endangered British society in yet another way, but the vote was, I contend, a form of social self-protection from self-regulating markets in money, trade and labour.

Ann Pettifor

Political Economist

Policy Research in Macroeconomics (PRIME)

London, Great Britain

Read the other essays on Brexit here:

Chris Hann

Brexit in the Valley of the Crow

Mikael Stigendal

Culture, Politics and the Economy:

From a happy to an awkward relationship

Kevin Morgan

Post Pandemic Brexit

Bob Jessop & Ngai-Ling Sum

Brexit as a double movement?

Matthew Watson

The Conservative Party's Impossible Brexit Politics

of 'Habitation vs. Improvement'